The COVID Pandemic Could Lead to 75,000 Additional Deaths from Alcohol and Drug Misuse and Suicide

Report Calls for Increased Investment to Improve Access to High Quality Mental Health Services

Oakland, Calif. (May 8, 2020) – Alongside the thousands of deaths from COVID-19, the growing epidemic of “deaths of despair” is increasing due to the pandemic—as many as 75,000 more people will die from drug or alcohol misuse and suicide, according to new research released by Well Being Trust (WBT) and the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care.

The brief notes that if the country fails to invest in solutions that can help heal the nation’s isolation, pain, and suffering, the collective impact of COVID-19 will be even more devastating. Three factors, already at work, are exacerbating deaths of despair: unprecedented economic failure paired with massive unemployment, mandated social isolation for months and possible residual isolation for years, and uncertainty caused by the sudden emergence of a novel, previously unknown microbe.

“Undeniably policymakers must place a large focus on mitigating the effects of COVID. However, if the country continues to ignore the collateral damage—specifically our nation’s mental health—we will not come out of this stronger,” said Benjamin F. Miller, PsyD, chief strategy officer, WBT. “If we work to put in place healthy community conditions, good healthcare coverage, and inclusive policies, we can improve mental health and well-being. With all the other COVID-related investments, it’s time for the federal government to fully support a framework for excellence in mental health and well-being and invest in mental health now.”

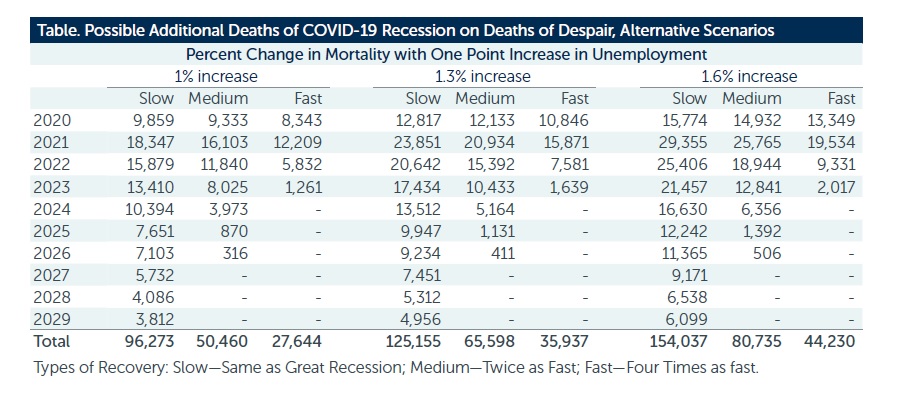

The study combined information on deaths of despair from 2018 as a baseline (n=181,686), projected levels of unemployment from 2020 to 2029 and then estimated the additional annual number of deaths based on economic modeling. Across nine different scenarios, the additional deaths of despair range from 27,644 (quick recovery, smallest impact of unemployment on deaths of despair) to 154,037 (slow recovery, greatest impact of unemployment on deaths of despair), with 75,000 being the most likely. When considering the negative impact of isolation and uncertainty, a higher estimate may be more accurate.

The analysis also includes potential increases by state and for select counties.

“These are uncertain times, unprecedented. Unfortunately, for too many, this uncertainty may lead to fear, and fear may give way to dread,” said Jack Westfall, MD, MPH, director of the Robert Graham Center. “We try to provide as much certainty as possible to shed some light on our path. We must also make our relationships certain, regardless of the uncertain facts and figures of the day.”

To prevent a disastrous wave of deaths of despair, the brief suggests several policy solutions, including figuring out how to ameliorate the effects of unemployment, making access to care easier, and how best to integrate care. In fact, these solutions should also serve to prevent drug and alcohol misuse and suicide during more normal times.

- Employment: Central to many of the problems in our communities will be the need to find work. Unemployment is an undeniable risk factor for suicide and drug misuse as well as decrease in overall health status. To this end, policy solutions must focus on providing meaningful work to those who are unemployed. Service can be a powerful antidote to isolation and despair, and COVID-19 offers new and unique opportunities to employ a new workforce – whether that be through contact tracing – helping local public health department track the virus – or through community health service where a new corps of community members are employed to provide help to those in the most need.

- Make accessing care easier: Care, especially primary and mental health care, has historically been fragmented. Individuals have had to work harder to get the care they need, and often that care is not delivered in a timely or evidence-based fashion. If COVID-19 has highlighted anything about our current delivery system, it’s that asking people to come to a clinic or a hospital is not always the best approach. Policies that support creative opportunities for care delivered at home—virtually or in-person—will provide comfort and safety. The idea of a home visit or a house call is not a new one, and, for professions like primary care, can be a major benefit. The artificial walls we have created around who can be seen where, by whom, and for what, have not been proven to work effectively for mental health.

- Integrating care: Care that is fragmented only creates roadblocks for patients and families. Referrals, prior authorizations, and other administrative barriers lead to frustration by all parties, including clinicians. Bringing mental health and addiction care into the fabric of primary and clinical care as well as community settings is essential. This requires vision, alignment with a framework, and a method for holding key stakeholders accountable for person-centered outcomes.

You can access the full analysis here.

###

Well Being Trust is a national foundation dedicated to advancing the mental, social, and spiritual health of the nation. Created to include participation from organizations across sectors and perspectives, Well Being Trust is committed to innovating and addressing the most critical mental health challenges facing America, and to transforming individual and community well-being. www.wellbeingtrust.org. Twitter: @WellBeingTrust

The Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care works to improve individual and population health by enhancing the delivery of primary care. The Center staff generates and analyzes evidence that brings a family medicine and primary care perspective to health policy deliberations at local, state, and national levels. Founded in 1999, the Robert Graham Center is an independent research unit affiliated with the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). The information and opinions contained in research from the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of the AAFP.