Caring for children’s mental health needs in — and out — of the emergency department

A collaboration in Oregon could be a model for dealing with a troubling national trend

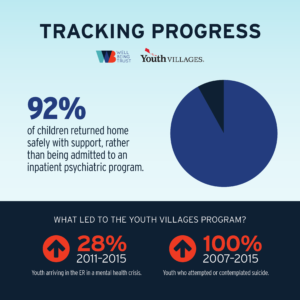

Across the United States, emergency departments have seen a troubling rise in the rates of children and youth arriving in mental health crisis — 28% increase from 2011 to 2015. Within that overall trend, emergency department visits by young patients who have attempted or contemplated suicide doubled between 2007 and 2015. Visits by children and teenagers who’ve deliberately physically harmed

Strained emergency department staff are struggling to keep up with these trends, says Andrew Grover, executive director of Youth Villages Oregon, which supports youth with emotional and behavioral issues. And, families with children who are suicidal, or dealing with other serious mental conditions or substance misuse issues, often leave the emergency department in need of intensive support, something hospital social workers typically are unable to provide.

“Families are overwhelmed with pain, grief and confusion when their children are contemplating suicide and even the most competent people are not good on following up on plans,” Grover says. “They’re just surviving.”

To deal with the growing problem and make sure families are connected to the proper resources, several Oregon hospitals, including Providence St. Joseph Health’s Providence St. Vincent Medical Center in Portland, Oregon, have asked Youth Villages Oregon for help. In response, the organization adapted a mental health crisis response program originally developed by Youth Villages in Tennessee. In the Oregon program, members of a team of eight family intervention specialists are on call 24 hours a day. Within an hour of a young patient’s arrival in the emergency department with a behavioral health issue, Youth Villages staff are on the scene to evaluate the young person, recommend a treatment plan and follow up for two weeks after discharge, if the family agrees.

“We become a part of the hospital team, but are also able to work beyond the walls of the hospital in the weeks following a family’s

Roots of the crisis

The partnership has a number of goals: Ensure the youth and families get what they need to safely manage the crisis, establish stable connections to longer term treatment, avoid unnecessary hospitalizations, and prevent these families from needing to come back to the emergency department for help. The team also works to get children out of the emergency department as quickly as possible, because it’s not a good environment for children in mental health crisis.

In pursuit of those outcomes, the family intervention team thoroughly assesses the young person’s condition and needs, says Kandi Shearer, Youth Villages Oregon’s assistant director of community services.

“We’re unique in our capacity to gather information not only from the youth, but also the parent or caregiver, emergency department staff, and/or community providers youth have worked with,” she says. “We have a really good relationship with the schools, and we call them right away. By speaking to all those people, we get a clearer picture of what’s going on so we can make the best recommendations for care.”

For example, if the root cause of the child’s distress can be traced back to school, Shearer and her colleagues meet with parents, school administrators and the child at school and make a plan to reduce triggers in that environment, as well as at home.

“We work on a safety plan with every family, but we also come up with a plan to reduce the factors that led to the crisis,” she says.

Tracking progress

Since the program launched in January 2017, it’s served more than 600 families a year and made a big difference, says Aaron Baker, PsyD, behavioral health outcomes program manager at Providence Oregon.

- The rate of children staying in the Providence St. Vincent emergency department for 12 hours (or longer) during emergency visits for behavioral health complaints decreased 23% from 2016 to 2019.

- During the same period, the rate of children in the emergency department for a behavioral complaint who stayed 24 hours (or longer) also decreased by more than half (53%).

- In three years, the number of children with a behavioral health issue who visited the emergency department and returned within 7 days decreased by 60 percent.

- 92% of children return home safely with support, rather than being admitted to an inpatient psychiatric program.

“There’s a lot of value to the education and support Youth Villages gives families after they go home,” Baker says. “Transitions are hard and getting connected to care is hard. If you can have that support and get connections going, then things can improve, and the family doesn’t have to go back to the hospital for another behavioral health emergency.”

“Our partnership with Youth Villages Oregon is a wonderful model for supporting families during and after their visit to the emergency department, at what is an incredibly stressful time,” says Robin Henderson, PsyD, Providence Oregon’s chief executive for behavioral health and Providence St. Joseph Health’s clinical liaison to the Well Being Trust. “But to make sure every child gets the right level of behavioral health treatment, communities must have a range of programs available.”

Warning Signs of Suicide

- Talking about wanting to die or to kill themselves.

- Looking for a way to kill themselves, like searching online or buying a gun.

- Talking about feeling hopeless or having no reason to live.

- Talking about feeling trapped or in unbearable pain.

- Talking about being a burden to others.

- Increasing the use of alcohol or drugs.

- Acting anxious or agitated; behaving recklessly.

- Sleeping too little or too much.

- Withdrawing or isolating themselves.

- Showing rage or talking about seeking revenge.

- Extreme mood swings.

—National Suicide Lifeline, 1-800-273-8255